Copyright Basics, created by Wilson College Library

Copyright refers to laws to protect the works and the rights of authors. These laws determine how or if someone else’s protected work can be legally copied, shared, performed, reused, or modified. Copyright infringement means copying or distributing someone else’s copyrighted material without permission. As soon as you create something that is your own work, such as a short story you’ve written or a video, you hold that work’s copyright in the United States.

Copyright can also be sold or licensed to another person or company, who then has control over what happens to the copyrighted content. For example, authors are often required to sign over their copyright upon publication, effectively handing over the rights to the companies that publish their work. This model enables publishers to charge outrageously high prices for journals, books, and textbooks. This is also why you cannot stream the tv series you like on every platform, and why Nintendo doesn’t let you livestream their video games.

Not all creative works are copyrighted. Works that are not protected by copyright are in the public domain. This means that you don’t have to ask for permission from a copyright holder to reuse the content. Materials in the public domain typically fall into one of two categories.

Does this mean that you can copy content from a US government website, such as this image from NASA, without asking for permission? Yes, you can!

Can you use it in an assignment without citing the source? No, that would be plagiarism. It’s important to always credit the source, regardless of whether or not it is in the public domain.

You can find a lot of public domain works on the internet using tools like Google Books and searching for works published 95 years ago or earlier.

Most works are under full, “all rights reserved” copyright. This means that they cannot be reused in any way without permission from the copyright holder. One way you can get permission to use someone else’s work is through a license, a statement or contract that allows you to reuse a copyrighted work in specific circumstances. For example, the copyright holder for a popular book might sign a license to provide a movie studio with the rights to use their characters in a film.

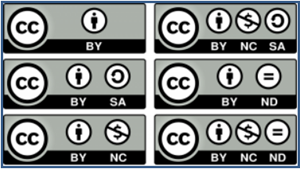

Creative Commons licenses are a type of copyright license that lets the creator specify the ways others can reuse their work. They were created to encourage sharing by making it easy to identify which works can be shared. These licenses help users understand what they can and can’t do when reusing someone else’s work.

There are six Creative Commons licenses, each with different rules, and attaching a license to your work lets others know how they may use your material. For example, a creator can use one type of Creative Commons license to specify that others can reuse their work but not make money off of it. Alternatively, they might use a license that says users cannot modify their work in any way. Want to learn more? Explore these licenses on the Creative Commons website.

Popular sites like YouTube, Wikipedia, Flickr, and many others have used Creative Commons licenses for years. You can even search for images available under a Creative Commons license using Google Image Search.

Copyright affects you both as a user and creator of information.

As an information user, you need to know:

As an information creator, you need to know:

If you want to learn more about copyright law, checkout copyright.gov from the U.S. Copyright Office is a good place to start.

Because plagiarism and copyright infringement are both related to the ethical reuse of ideas and content, it can be confusing to understand where one ends and the other begins. One way to differentiate between the two is to examine the consequences of each.

When someone commits copyright infringement by sharing materials without permission from the copyright holder, this is a legal offense and can incur financial penalties. The consequences of these actions could include having something taken down from the internet, fines, or even jail time.

In contrast, when someone commits plagiarism, they haven’t broken any state or federal law and can’t be thrown in jail for that offense. However, because plagiarism involves stealing someone else’s ideas, it’s still unethical. For students, this can lead to failing a course or being kicked out of college. After graduation, plagiarism could lead to the loss of professional credibility and even get them fired.

Now that you understand some basics, let’s compare plagiarism and copyright infringement in the context of being a college student. Building off of the works of other researchers is a core component of scholarship. You don’t need anyone’s permission to quote or cite their work, but you do need to carefully cite your sources to avoid committing plagiarism. Avoiding copyright infringement is more complicated.

Let’s say you want to include some copyrighted photographs (not your own) in a paper you’re writing for a class assignment. Your professor will read your paper, and perhaps your paper will be discussed in class, but it will not be shared outside of the classroom. You carefully cite the photographs in your paper, so you know you are not plagiarising, but are you infringing on copyright? No, this is not considered copyright infringement because the photos will only be shared in your classroom.

The situation is very different if you want to reuse those photos outside of your class. Not only would you need to cite the images properly, but you would also need to contact the copyright holder and ask for permission to reuse their photographs. The copyright holder would get to decide whether to grant that permission and determine any fees or conditions for reuse. Failing to comply with those conditions would be copyright infringement and put you at risk to be sued.

Fair use refers to specific legal exceptions that let you use copyrighted material without having to ask for permission or pay any fees. One reason fair use exists is to make it easier for copyrighted material to be used in universities and other educational settings, where these materials are taught, shared as course readings, and used for research. Another example of fair use is when an artist or musician reuses or references someone else’s creative work in something they create (e.g. the parody songs of “Weird Al” Yankovic).

Fair use is determined by analyzing four factors:

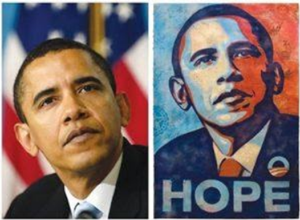

This means that not every reuse of copyrighted works is considered fair use. In one high profile example, graphic designer Shepard Fairey based his well-known “Hope” poster on a photograph of Barack Obama that was taken by photographer Mannie García, who was working for the Associated Press (AP).

Fairey did not acknowledge his source. When the source was revealed, Fairey tried to defend his work as fair use. However, the AP disagreed and took Fairey to court, where a judge decided Fairey’s poster violated copyright law and was not fair use. Below, we review the four factors for determining fair use in more detail and how Fairey’s work fails to meet them.

This factor considers what you’ll be doing with the original work you use. Fair use favors uses that:

In the case of the “Hope” poster, the graphic designer attempted to transform the photograph by color blocking it; however, he did not significantly transform the photo from the original. In addition, since the original was not cited or acknowledged, it would be difficult to consider Fairey’s work as a commentary or critique of the original.

This factor considers the purpose and type of the original work you want to use. Specifically, fair use favors uses that:

Using someone else’s artistic work, such as Mannie García’s photograph, is less likely to be considered fair use. Copyright law was created to protect authors and artists so that they would create more. Mannie García’s photograph was his own creative expression, another reason why the judge determined that Fairey’s derivative poster was not fair use.

This factor considers the amount of the original work you are reusing, and how substantial that portion is. Fair use supports the use of a small or less important portion of a work. Specifically, fair use favors uses that include:

Fairey’s poster used nearly all of Mannie García’s photo. While the poster omits the flag in the background of García’s photo, the most substantial part, Barack Obama’s face, was included in its entirety. This does not support the argument that his poster was fair use.

This factor considers whether your use could impact the sale and perception of the original work. Fair use favors uses that:

The photograph in this example was Mannie García’s original creation. However, Shepard Fairey’s derivative work became so famous that most people would never know the poster was based on someone else’s work. In other words, you could say that Mannie García’s photograph and creative vision were devalued.

As we’ve seen in this example, fair use is determined by considering not one or two but all four factors. One common misconception is that everything is fair use if the material is used for an educational purpose. That’s an oversimplification. The four key factors for determining fair use should all be considered together.